Going on field trips is just about every kid’s favorite thing to do at school. A chance to get out of the classroom and have some real fun! I don’t know if I have ever heard a student complain about heading out on a field trip. While field trips should be fun, they should still be purposeful. The students should walk away from a field trip with more knowledge than they had walking in. Unfortunately, I don’t think that this is always they way things turn out.

Last week the middle years cohort had a chance to take a field trip of our very own. I must admit, this late in the semester when all assignments are assigned and due, I didn’t see the purpose in taking a field trip. Aside from this blog post here the trip really had no bearing on me. I thought I for sure had more important things to do for two hours, but away I went anyway. Although I have lived in Regina for 6 years I had never been to the Royal Saskatchewan Museum. I think that students who have never been to the place you are taking them are always going to be more engaged. When there are only so many things to go see in and around Regina, I think that a lot of students end up going to the same places in multiple grade levels and will take away less and less each time. However, as it was my first time I was interested to see what they were presenting.

We arrived and met in the lobby where we were given a handout that is available to all student attendants from grade 4-8 who are visiting the First Nations Exhibit. We started through the exhibit on the hunt for the answers to the questions. A group of us got about half way through the whole thing when we realized that we hadn’t even seen anything in the first half except what some of the placards said to answer the questions. We decided to put away our papers and just actually view the displays. As it turns out, this was the point of the activity. Giving students such a rigid task almost ensures that they will only observe what is being directly asked on the handout. This is what the majority of the class did, including myself for the first half. When we met as a class at the end of the exhibit we talked a bit about what happened and how that handout is maybe not the most helpful learning tool. Then we got a new handout, one that didn’t ask for such specific answers, and took another walk through the entire exhibit.

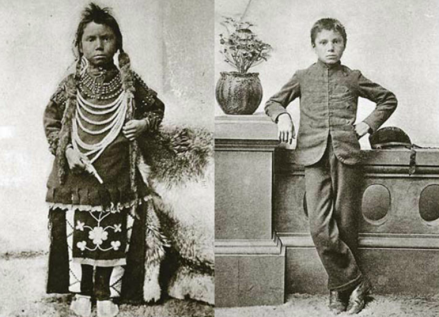

On the second time we just really looked at the whole thing. Took in all the detail, the language, and the story being told. I was astonished by the detail in each display. The four hunting seasons was my absolute favorite and I found new details every time I looked at it. Another really interesting piece was the quilt made by students at a residential school. At first I was kind of impressed by the skill, but then I thought about it a little deeper. The images depicted were strange and must have been strange to those who were being told to make them. While there are a few tipis and other First Nations depictions, a lot of the images were of foreign objects like elephants and there were quite a few depictions of European men with pointing fingers. A student project could be developed from that artifact alone.

At the end of our second time through the museum we had a discussion about what we noticed. A lot of it was negative. The language mostly talks in past tense, as if the First Nations people no longer exist. The meeting of First Nations with the European people is made out to be only a positive thing in the lives of the First Nations people, residential schools are not even mentioned (the blanket is described as being a quilt made by the students at a school on a reservation) and the outbreak of smallpox is described as something that just happened to the First Nations peoples. The Treaties get a simple mural on the wall and again discuss only the positive things that were to have happened. I agree with all those statements and think there are definitely things that could be done to improve the exhibit. The placards are all outdated and there are

I do not however think that the exhibit can only be described as negative. Most museums focus on past events, and there is always going to be a level of interpretation, but I still think that this exhibit on the First Nations people is better than not having an exhibit at all. If I were to take my students here I would make sure to discuss critical thinking beforehand. I would definitely not use the handout that is supplied by the Royal Saskatchewan Museum’s website. I think the question that I would pose to my students before is simply “What did you notice about the museum that you think was done well or that could be improved upon?” I do not think that you could or should try to take students into this museum exhibit, or any field trip, without some kind of background knowledge about the topic. Field trips should be a place where students can build on their existing knowledge while they are having fun and seeing something new.